half a century

My darling Jack is turning fifty in a few weeks time. Now, a milestone such as that calls for an extra special hand-made present, but with the end of semester looming, and mountains of marking about to flood in, it'll be cutting it fine to get the project I have in mind completed in time. I'll give it a good try though!

What I'm planning to make is a medieval pop-up book using Jack's beautiful translation of a poem by Marie de France called 'The Nightingale'. It's a tragic narrative poem about the doomed love between a knight and the beautiful wife of his neighbour, a jealous knight who exacts a cruel revenge on the pair.

I've copied Jack's English translation of the poem below. If you're a sentimental sort like me, make sure you have a tissue on hand before you read it:

The Nightingale

Translated from Marie de France’s Laüstic (c.1180)

by Jack Ross

The story that I’ll tell today

the Bretons made into a lay:

Laüstic they called the tale

French rossignol – or nightingale.

By Saint Malo there was a town

famed far and wide, of great renown.

Two knights lived there in luxury:

fine houses, servants, horses, money.

One had married a lady fair

wise, discreet and debonair

(she kept her temper wonderfully

considering her company).

The other was a bachelor

well known among the townsfolk there

for his courage and his courtesy

and for treating people honourably.

He went to all the tournaments,

(neglecting solider investments)

and loved the wife of his neighbour.

He begged so many boons from her

she felt he had to be deserving

and loved him more than anything –

as much for the good he’d done before

as for the fact he lived next door.

Wisely and well they loved each other

avoiding undue fuss and bother

by keeping everything discreet.

This was the way they managed it:

because their houses stood side by side

there wasn’t much they couldn’t hide

behind those solid walls of stone.

The lady, when she was alone,

would go to the window of her room

and lean across to talk to him.

They swapped small tokens of their love:

he from below, she from above.

Nothing interfered with them.

No-one noticed, or poked blame.

However, they could not aspire

to reach the peak of their desire

because there was so strict a guard

on all her movements. It was hard,

but still they had the consolation

of leaning out in any season

to exchange sighs across the gap.

No-one could stop that access up.

They loved each other for so long

that summer came – green buds, birdsong:

the orchards waxed into full bloom

bringing amorous airs with them,

and little birds carolled their joy

from the tip of every spray.

The knight and lady of whom I speak

felt their resistance growing weak –

when love wafts out from every flower

it’s no surprise you feel it more!

At night, when the moon shone outside,

she’d leave her husband sleeping, glide

wrapped only in a mantle, till

she fetched up at the window sill.

Her lover did the selfsame thing,

sat by his window pondering,

and there he’d watch her half the night.

This simple act gave them delight.

So often did she do it that

her husband started to smell a rat.

He asked her where she went at night

and why she rose before first light.

“Sir,” the lady said to him,

“It’s more than just a passing whim.

I hear the nightingale sing

and have to sit here listening.

So sweet his voice is in the night

to hear it is supreme delight,

the joy it gives me is so deep

I can’t just close my eyes and sleep.”

Her husband heard this glib reply

and laughed once: coarsely, angrily.

He thought at once of thwarting her

by catching the bird in a snare.

His serving men were rounded up

and put to work on net and trap

to hang on every single tree

in his entire property.

They wove so many strings and glue

the bird was caught without ado.

When the nightingale was caught

they brought it living to the knight.

This exploit pleased him mightily;

he went at once to see his lady.

“Lady,” said he, “where are you?

Come here; this concerns you too.

I’ve snared that little bird, whose song

has been keeping you awake so long.

Now you can sleep the whole night through,

Rest easy: he won’t bother you.”

When the lady heard him speak,

she felt crestfallen and heart-sick.

She asked a favour of her lord,

if she could have the little bird.

At that he did something macabre,

snapped its neck in front of her,

and threw the body at her dress

to bloody it above the breast.

Then he stalked out of her door.

The lady picked it from the floor,

and sobbing, called a living curse

on those who’d made her prison worse

by hanging nets in every tree

to snare the bird who set her free.

“Alas,” said she, “I am undone!

I can no longer rise alone

and sit by the window every night

to watch my lover, my sweet knight.

There is one thing I’m certain of:

He will believe he’s lost my love

unless I tell him what’s occurred.

By sending him the little bird

I’ll warn him what’s befallen me.”

She wrapped it in embroidery

and cloth of gold, and asked a page

to deliver this last little package

to her friend who lived next door.

The page walked over to their neighbour,

saluted him on her behalf,

and gave what he’d been asked to give:

the bird’s body, the lady’s message.

When he understood the damage

his love had done to this lady

the young man did not take it lightly.

He had a cup made out of gold,

studded with precious stones, and sealed

against the corrosive outer air.

He put the nightingale in there,

then shut it in its little tomb

and took it everywhere with him.

The tale could not be hidden long

so it was made into a song.

Breton poets tell the tale;

they call it “The Nightingale.”

*********************

You can dry your eyes now and I'll tell you about my ideas for the pop-up book.

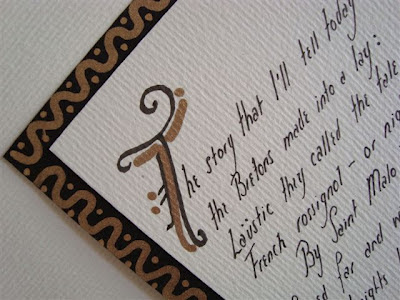

The book will be a combination of illuminated, hand-written text panels (my first attempt above) with a central pop-up form on each page, including one pop-up spread with the knight and the damsel gazing at each other from the windows of their neighbouring castles; one featuring a close-up view of the tree-tops with nets to catch the mightingale; one close-up of the woman holding the dead nightingale with its blood staining her dress, and the final spread of the book will show the jewel-encrusted tomb for the bird.

The design process I employ for pop-up books always begins with a couple of rough sketches to work out how the text and pop-up element will fit together on the page:

Then I make a mock-up:

I plan to make the castle taller, and possibly add a centralised tree to the composition. I also need to add the figures of the damsel and the knight at the open windows. I found a couple of books at home with gorgeous reproductions of medieval illustrations that I'm using as sources for my medieval pop-up book. Here are a few images from them:

I love the simple decorated borders in the images and I especially love the naive quality of the figures, perfect for someone like me who has the drawing ability of an eight year old! The images below have provided the main inspiration for the pop-up book:

I'll keep you posted on developments with this special book project over the next few weeks. I really hope that 'The Nightingale' pop-up book looks as cool in real life as it does in my imagination! Things seldom do!

Comments